Khachkar Dedicated in Berlin

May/03/2016 Archived in:Culture | Armenian Genocide

By Muriel Mirak-Weissbach

The dedication ceremony opened with remarks by Dr. Raffi Kantian, President of the DAG, and Armenian Ambassador Raffi Kantian. As Dr. Kantian recounted, it was on the very same place on May 14, 1919, that the first commemorative service in honor of the memory of the genocide victims took place on German soil. Such an event “would have been unthinkable during World War I, due to Imperial Germany’s alliance policy” he said; but “the young Weimar Republic made it possible.”

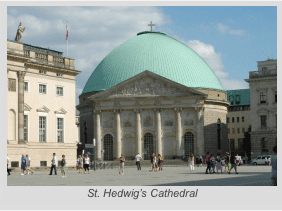

An article published by the DAG’s journal at the time had reported that the mass had been celebrated by members of the Mkhitarist Order from Vienna, all in the Armenian language, and sung with the participation of the St. Hedwig’s choir. The article had noted that the service constituted a protest against the Turkish crimes, a protest delivered in a dignified manner. It wrote, “The fact that it took place in the capital of the German Empire, which had been a wartime ally of the Ottomans, gave this protest heightened significance and emphasis.”

Why had this particular church hosted that service? Kantian placed it in the context of the initiative taken in September 1915 by then-Pope Benedict XV, who had sent a hand-written letter to Sultan Mehmet V condemning the massacre of Armenians. There were several leading Germans who also raised their voices, among them Archbishop Felix Cardinal von Hartmann and lawmaker Matthias Erzberger. It may be that Erzberger, who was later to serve as minister in the first Weimar Republic government, attended the church service, Kantian said. And it is certain that Elly Heuss-Knapp, wife of the later President Theodor Heuss, was there; her mother was in fact Armenian.

Kantian highlighted the role played by Johannes Lepsius in informing German public opinion of the massacres in his famous Report on the Situation of the Armenian People in Turkey of 1916, which, though soon confiscated, had a decisive impact. Not far from St. Hedwig’s Cathedral is the Berlin Cathedral, where, as Kantian recalled, a commemorative mass was celebrated last year. Following that service, German President Joachim Gauck held an unforgettable address, in which he spoke of the genocide in those words, a prelude to the historic debate that took place in the Bundestag the next day.

The khachkar, Kantian continued, should be seen as “a symbol of peace.” It is dedicated to “the memory of the destiny of innumerable Armenians who fell victim to the nationalist madness of the leadership elite of the Ottoman Empire,” as well as in memory of the other victims. He presented the khachkar also as a “symbol, carved in stone, of brotherliness, without which there would not have been a church service almost a hundred years ago, or a khachkar here today.” Special thanks went to Anna and Artur Varchapetyan, whose generosity made the stone cross possible.

Ambassador Sambatyan said he was filled “with joy that does not find words” that the khachkar was being dedicated. He added his hope that “many, especially young people, will recognize this place – here in the heart of the German capital – as a memorial, and look into the events of 1915, the Armenian genocide in the Ottoman Empire, and gain knowledge they have not been able to find so far in school books and history lessons.”